Publications

Consent, information for decision-making and the Patient Journey by Fiona Tito Wheatland

19 August 2019

Fiona Tito Wheatland is the HCCA consumer representative on the Consent Working Group with Canberra Health Services. Fiona has been drafting materials to support the discussions. We thought that this document sets out consent issues as they relate to the patient journey really well and others would be interested to read this.

Fiona Tito Wheatland is the HCCA consumer representative on the Consent Working Group with Canberra Health Services. Fiona has been drafting materials to support the discussions. We thought that this document sets out consent issues as they relate to the patient journey really well and others would be interested to read this.

There are a number of processes covered by what people commonly call consent in health care in Australia.

- At its simplest, a patient provides consent for treatment, which prevents them then claiming that giving an invasive treatment was an assault or trespass to their person. The emergency exception allows a doctor to treat a patient without consent and to be exempt from a claim of trespass to the person, where the patient was unable to consent and the treatment is required to prevent death, serious damage to the patient’s health, or significant pain or distress.

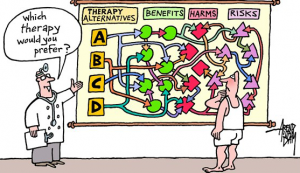

- The common law also requires that a patient be given information on the options, benefits and risks of treating their health care needs. If the information is not provided then a doctor may be considered to be negligent for failing to give the information, even if the treatment was not provided negligently. The High Court has recognized two arms to this test: the so-called “objective” arm, where the test is that the risk was likely to be material to a reasonable patient in the circumstances of the patient. The “subjective” arm extends this to require disclosure of risks which might be considered material by that particular patient.

- There is a general “consent” often signed on admission to a hospital, which is in addition to the specific consent noted in paragraph (1). It may cover other information eg. about sharing information but does not replace the need for the above kinds of “consent”. It is arguable that such a consent form is a “framework” of the hospital’s general administrative arrangements (eg. whether the patient is a public or private patient, approval for providing their treating information to a primary care provider) and possibly may be linked to the systemic quality assurance obligations of the hospital to all its patients.

- Where someone is either too young or otherwise not able to provide consent, because they are unconscious, not legally competent because of physical, mental or intellectual impairment, whether permanent or temporary, consent may be able to be provided by someone else. There are a range of common law and legislative bases for this, and it is understood that this will be the subject of another paper.

It is important, therefore in looking at consent processes that these are recognised as a mixture of:

- information giving and receiving;

- the opportunity to ask questions and clarify issues/concerns;

- the ability and intention to make a decision; and

- the act of agreeing to a particular course of action.